How Life creates the new from the old.

Creativity & Digestion 1: Introduction

Creativity & Digestion 2: Mouth & The Eating of Earth

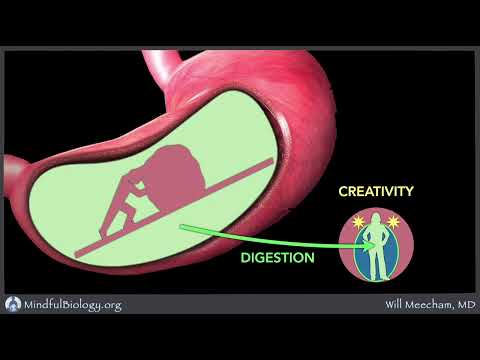

Creativity & Digestion 3: Stomach & Relationship

Creativity & Digestion 4: Intestines & Completing the Cycle

Creativity & Digestion 5: Meditations & The Earth, Walking