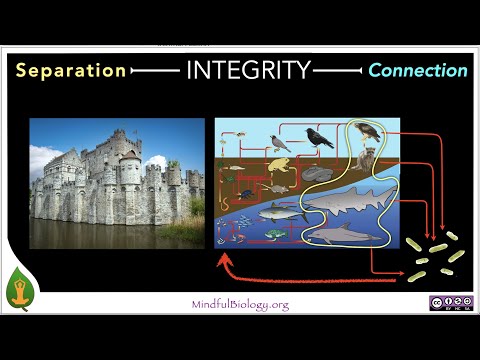

How Life thrives amidst change and turmoil.

Integrity 1: Introduction

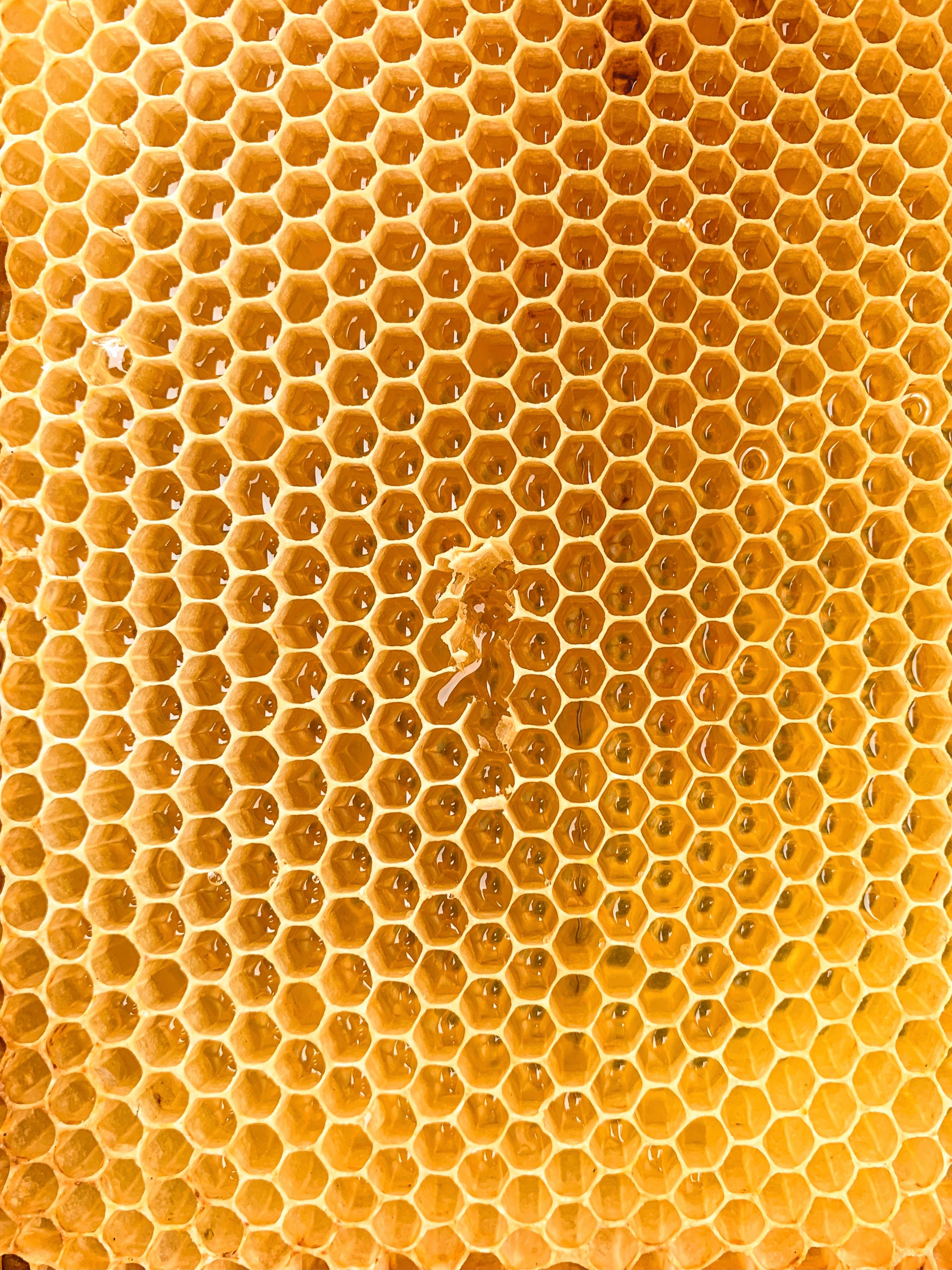

The Integrity of Life on earth.

Integrity 2: Mobile Integrity

Moving through Life with Integrity.

Integrity 3: Emotional Integrity

Understanding and managing emotions.

Integrity 4: Immune Integrity

The immune system and navigating Life.

Integrity 5: Deep Integrity

Intelligence and the future of civilization.